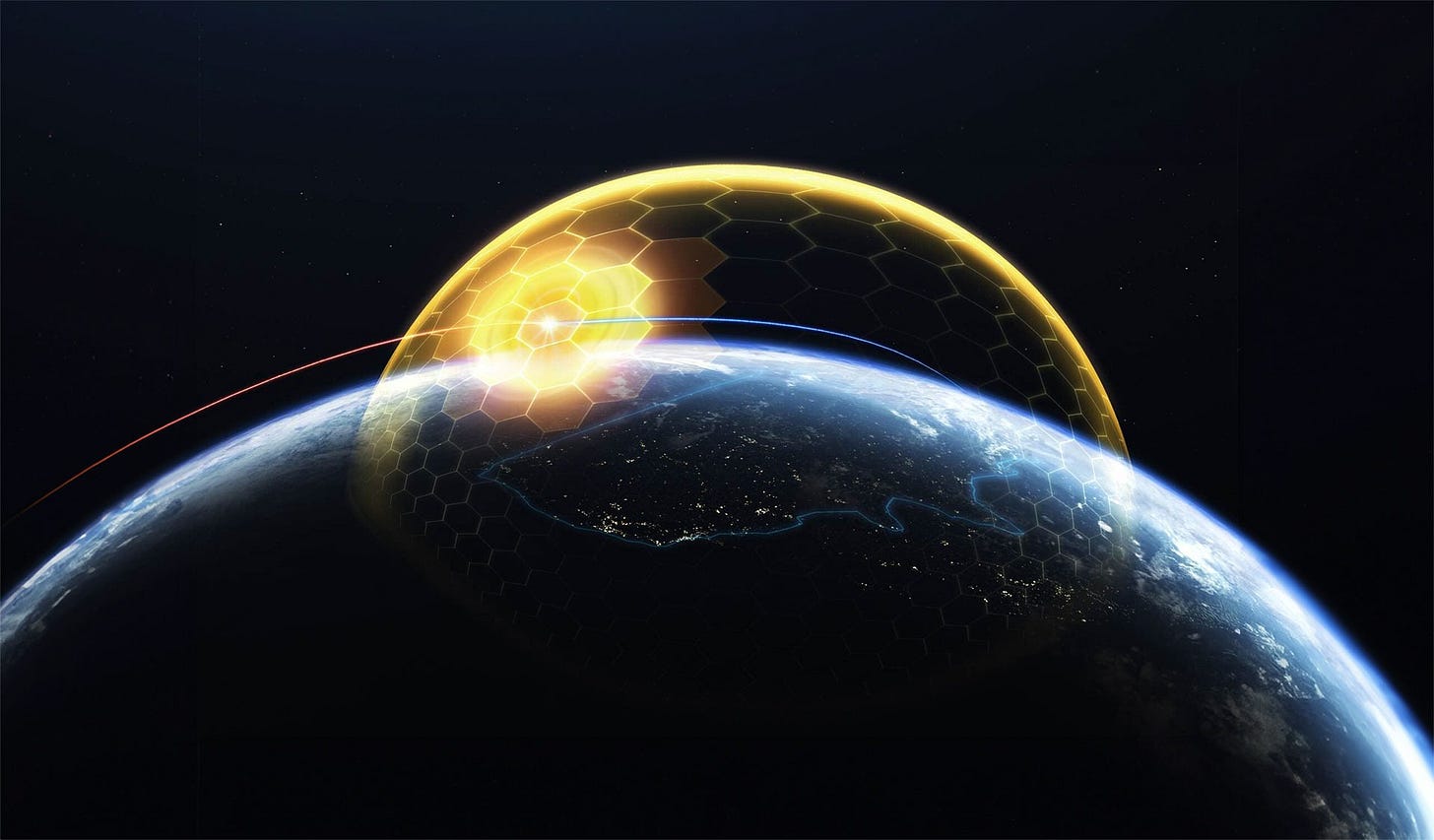

The Golden Dome Initiative: Strategic Ambitions and Practical Challenges in U.S. Missile Defense Policy

The Trump administration's "Golden Dome" executive order represents a paradigm shift in U.S. missile defense strategy, aiming to create a comprehensive shield against all foreign aerial threats to the homeland, including nuclear-armed ballistic missiles from Russia and China. This policy breaks with decades of bipartisan consensus that prioritized limited defenses against rogue-state attacks while acknowledging the impracticality of neutralizing peer adversaries' strategic arsenals. The initiative resurrects controversial technologies like space-based interceptors and directed-energy weapons while expanding existing systems such as the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) network. However, technical limitations in discriminating warheads from decoys, astronomical costs for space-based architectures, and the destabilizing impact on nuclear deterrence frameworks underscore the proposal's fundamental flaws. Given cost estimates for key components range from $32 billion to $179 billion over 20 years and adversarial nuclear modernization programs accelerating in response, the Golden Dome risks triggering a new arms race without delivering meaningful protection.

Historical Evolution of U.S. Missile Defense Policy

From the ABM Treaty to the Post-9/11 Paradigm

The 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty codified mutual vulnerability between the U.S. and Soviet Union, recognizing that unlimited missile defense deployments would fuel offensive arms racing. This strategic stability framework persisted until President George W. Bush's 2001 withdrawal, which prioritized developing defenses against emerging threats from North Korea and Iran rather than peer competitors. Subsequent administrations maintained this limited approach, focusing on regional theater systems like Aegis and THAAD while cautiously expanding the GMD system’s capacity against North Korean ICBMs.

The 2019 Trump Missile Defense Review marked a transitional phase, endorsing advanced defense research while explicitly excluding Russia and China from homeland protection objectives. This nuanced stance aimed to balance technological ambition with strategic stability considerations, acknowledging that comprehensive defenses against peer nuclear arsenals remained technologically infeasible and politically destabilizing.

The Golden Dome’s Radical Departure

The 2025 executive order dismantles these guardrails by declaring defense against "any foreign aerial attack" as policy, including strategic nuclear strikes. This doctrinal shift implicitly targets Russian and Chinese arsenals, discarding previous administrations’ careful distinction between rogue-state and peer threats. The Missile Defense Agency (MDA) now faces directives to integrate space-based interceptors, boost-phase defense architectures, and non-kinetic systems into a layered homeland shield—a vision exceeding even Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative in scope.

Architectural Components of the Golden Dome Initiative

Sensor Layer: Space-Based Tracking Networks

The Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS) and Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA) form the initiative’s eyes in the sky. Launched in February 2024, the first HBTSS satellites provide fire-control-quality tracking for hypersonic glide vehicles, while PWSA’s planned 300+ low-earth orbit satellites aim to maintain continuous target custody across all missile flight phases. However, integrating these constellations with terrestrial radars and command systems remains incomplete, risking gaps in the kill chain during mass salvos.

Interceptor Systems: Layered Defense Concepts

The Golden Dome envisions a three-tiered intercept architecture:

1. Boost-Phase Engagement: Space-based interceptors targeting missiles during vulnerable ascent

2. Midcourse Defense: Expanded GMD sites with new Next-Generation Interceptors (NGIs)

3. Terminal-Phase Systems: THAAD and Aegis Ashore batteries for final-layer protection

This "underlayer" approach theoretically increases engagement opportunities but compounds technical challenges. The MDA’s 2020 proposal to network Aegis, THAAD, and GMD failed Congressional approval due to interoperability concerns, yet the executive order mandates reviving this integration within 60 days.

Emerging Technologies: Directed Energy and Hypersonic Defenses

The initiative allocates $2.7 billion annually for high-energy laser development, targeting boost-phase intercepts and cruise missile defense. While advances in fiber laser efficiency (now exceeding 40%) enable megawatt-class systems, the American Physical Society estimates operational deployment against ICBMs remains 10-15 years distant. For hypersonic threats, the MDA is testing glide-phase interceptors with hit-to-kill vehicles capable of Mach 12 engagements, though test schedules slip due to thermal management issues.

Technical Hurdles and Operational Limitations

The Discrimination Dilemma

Midcourse defense remains plagued by inability to distinguish warheads from decoys—a problem former Undersecretary Michael Griffin concedes shows “no meaningful progress since 2010.” Advanced adversary countermeasures like cooled shrouds and multi-spectral decoys render GMD’s discrimination algorithms obsolete. Simulations indicate current systems could be overwhelmed by just 10 simultaneous warheads employing modern penetration aids.

Space-Based Interceptor Economics

Boost-phase defense proposals face prohibitive cost-exchange ratios. Defending against a 10-missile North Korean salvo would require 16,000 orbiting interceptors at $27 billion initial cost plus $4 billion/year in replenishment—a 1600:1 cost ratio favoring offense. Launch cost reductions to $1,000/kg still yield $12 million per interceptor, making sustained defense against peer arsenals economically unsustainable.

Laser Power Scaling Challenges

While 300 kW lasers now demonstrate cruise missile kills at 10 km ranges, ICBM boost-phase intercepts require 25 MW systems with 1,000 km engagement envelopes—a 83x power increase. Even with 5% annual efficiency gains, the American Physical Society projects operational deployment no earlier than 2035.

Strategic Stability Implications

Russian and Chinese Responses

Moscow has paralleled Golden Dome developments with its S-550 anti-satellite system and Avangard hypersonic glide vehicles, explicitly citing U.S. missile defense advances as justification. China’s nuclear arsenal expansion from 400 to 1,500 warheads since 2020 directly correlates with GMD site expansions, according to PLA doctrinal analyses. Both nations now prioritize MIRVed ICBMs and depressed-trajectory SLBMs to saturate defense systems.

Erosion of Arms Control Frameworks

The New START treaty’s collapse in 2026 and subsequent freeze in U.S.-Russian nuclear talks stem partly from Moscow’s insistence on including missile defenses in any new agreement—a non-starter for Golden Dome proponents. China’s continued refusal to engage in trilateral arms control talks further complicates crisis stability mechanisms.

Cost-Benefit Analysis and Alternatives

Budgetary Impacts

Congressional Budget Office estimates for comprehensive homeland defense range from $77-$179 billion over 20 years for cruise missile defense alone. Adding space-based interceptors and laser systems could push total costs above $300 billion—equivalent to three Ford-class carrier groups annually. These figures exclude operational costs like satellite replenishment and interceptor stockpile rotation.

Alternative Investment Priorities

1. Infrastructure Hardening: $12 billion could harden all CONUS nuclear command sites against 100-kt airbursts

2. Arms Control Incentives: Matching Russia’s 500-warhead arsenal would save $120 billion over 30 years compared to Golden Dome

3. Conventional Deterrence: 300 new B-21 bombers provide comparable coercive power at 1/3 the cost of midcourse defense expansion.

Conclusion: Recalibrating Missile Defense Policy

As the 2025 Defense Science Board review concluded, “The physics of strategic defense remain unfavorable; the geopolitics have grown worse.” If the Golden Dome initiative has a fatal flaw it lies not in questions surrounding its technical feasibility - as long as Elon Musk sticks around - it is in pursuing a purely technical solution to a political-strategic problem. The ABM Treaty’s architects recognized that no feasible missile defense can negate Russia’s 1,550 treaty-accountable warheads or China’s expanding arsenal. An alternative approach, which avoids further fueling the nuclear arms race through maximalist defenses, is a clear reinstatement of U.S. Policy’s distinction between theater and homeland systems, while resuming arms control engagement. Targeted investments in point defenses for critical infrastructure, combined with renewed transparency measures with adversaries, offer more sustainable security at lower cost and risk. However, President Trump, once fixated on an idea, just like the chief architect of his political vision, is all-in or nothing.