Licensing Is the New M&A: How Europe, and Ukraine, Are Rebuilding Defense Industrial Power

For much of the post–Cold War era, consolidation was the dominant strategic logic in defense. When governments or prime contractors wanted scale, speed, or access to new capabilities, mergers and acquisitions were the preferred instrument. Ownership conferred control, and control was how industrial power was built.

That logic is now shifting in Europe. And nowhere is the shift clearer, or more consequential, than in and around Ukraine.

As Europe accelerates rearmament under acute time pressure, licensing has taken on a new strategic role in how defense industrial power is built. Licensed production, technology transfer, and structured industrial partnerships are increasingly performing the function that M&A once served. They are expanding capacity, embedding suppliers locally, and accelerating delivery, often faster and with far fewer political and regulatory complications than outright acquisitions. In effect, licensing is becoming a substitute for consolidation in the areas that matter most: throughput, resilience, and speed.

To understand why this shift is happening, it is important to distinguish between two historically distinct meanings of licensing in defense technology.

The first is regulatory licensing. This refers to the export and import control regimes that govern who may access defense articles, services, and sensitive know-how. Frameworks such as ITAR in the United States and comparable export-control systems in Europe exist to prevent unauthorized transfer of military capabilities to foreign powers. For decades, this form of licensing functioned primarily as a constraint. It limited who could build what, where production could occur, and how technology could be shared across borders. In this sense, licensing was defensive and restrictive, designed to slow diffusion rather than accelerate it.

The second meaning of licensing is commercial technology transfer. Governments have long developed military technologies internally and then licensed those inventions to private industry for production and commercialization. In this model, the state retains ownership of intellectual property while granting manufacturers the right to produce and scale systems. Historically, this process was slow, bureaucratic, and peripheral to core procurement strategy. It existed alongside acquisitions and prime-led integration, not as a replacement for them.

What has changed is that these two forms of licensing have converged into an active industrial tool, and Ukraine has pushed this convergence further than any other defense actor.

Europe’s core defense challenge today is not primarily technological invention. In many critical domains, proven systems already exist. The binding constraint is industrial capacity. Stockpiles are depleted, lead times stretch into years, and supply chains remain fragile and nationally segmented. Procurement priorities have therefore shifted toward speed to production, security of supply, and domestic manufacturing presence. In this environment, who owns a company matters less than where systems are built and how quickly production can scale.

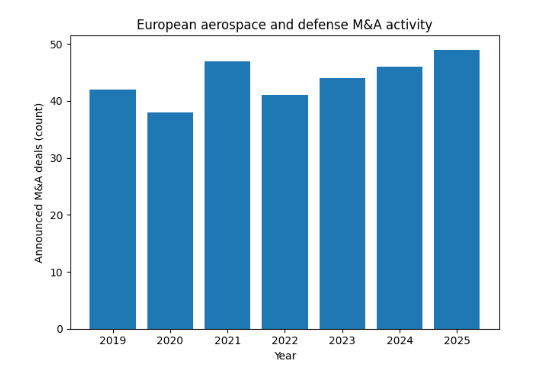

This reality weakens the appeal of traditional cross-border defense M&A. Even when strategically rational, acquisitions remain politically sensitive. They trigger national security reviews, parliamentary scrutiny, and public resistance framed around sovereignty and strategic autonomy. They are also slow to integrate. In a rearmament cycle defined by urgency, those frictions are costly.

Licensing and joint industrial structures offer a more tractable alternative. They preserve national ownership narratives while delivering tangible industrial outcomes. Manufacturing is localized, employment is created, and governments can credibly claim strengthened domestic capacity without approving a foreign takeover. For regulators and procurement authorities, these arrangements are easier to frame as cooperation rather than consolidation.

Air defense provides a clear European illustration. Rather than acquiring European missile houses outright, suppliers have increasingly pursued localized production through partnership structures. The establishment of a Patriot missile production facility in Germany through cooperation between Raytheon and MBDA reflects this approach. Production and know-how are embedded locally, while ownership remains unchanged. From a government perspective, the outcome resembles what an acquisition might have promised: domestic capacity, supply security, and long-term industrial presence, achieved without the political cost of consolidation.

Ammunition and energetics follow the same logic under even greater pressure. The urgent need to expand shell and propellant output has driven capacity expansion through joint ventures and licensed production rather than acquisitions. Rheinmetall’s industrial partnerships in Eastern Europe reflect a broader pattern. What matters is not who owns the factory, but whether output can be increased quickly and sustained domestically.

Ukraine, however, represents a qualitative leap.

In 2025, Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence confirmed that it had granted thirty licenses to manufacturers to use technologies developed directly by the Ukrainian military. These licenses cover electronic intelligence systems, counter-drone solutions against Shahed-type UAVs, and guided weapons with automated targeting and guidance. Systems produced under these licenses are already being delivered to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

This program is not an emergency workaround. It is an institutionalized model. A government resolution adopted in October 2025 established a formal mechanism for transferring state-developed military technologies into serial production while retaining intellectual property under state ownership. Instead of acquiring manufacturers, merging state entities with private firms, or consolidating suppliers, Ukraine licenses its combat-proven technologies to multiple producers simultaneously.

The result mirrors the functional objectives of M&A without its drawbacks. Capacity scales faster because multiple manufacturers can produce in parallel. Risk is diversified rather than concentrated. Innovation generated within the military is rapidly commercialized without ownership transfer. The state retains control over intellectual property while the industrial base expands horizontally rather than vertically.

Ukraine’s approach is especially instructive because it operates under conditions where speed, resilience, and redundancy are existential requirements. When output matters more than ownership, licensing is not a second-best solution. It is the optimal one.

This logic increasingly applies across Europe as well. Defense licensing is no longer limited to hardware. As warfare becomes more software-defined, licensing models are shifting toward AI-enabled systems, digital command architectures, and interoperable software platforms. Governments are demanding explainability, governance, and interoperability rather than bespoke, vertically integrated solutions. Licensing, rather than acquisition, is better suited to this modular, software-centric future.

None of this suggests that M&A is obsolete. Licensing is not a universal substitute for acquisition. It struggles where full design authority is essential, where export autonomy is critical, or where long-term system evolution requires unified control. In those cases, ownership still matters, and consolidation will continue to play a role.

But for the central challenge Europe now faces, and for Ukraine’s immediate reality, the rapid expansion and localization of defense industrial capacity, licensing, technology transfer, and structured industrial partnerships are increasingly doing the heavy lifting.

That is why licensing is starting to look like the new M&A. Not because ownership no longer matters, but because, in today’s Europe, and in Ukraine most of all, capacity matters more.