China's Restrictions on Rare-Earth Minerals Affecting the Pentagon

Over 78% of U.S. military weapons rely on Chinese materials.

China is initiating restrictions on the export of rare-earth minerals critical to U.S. military capabilities—a vulnerability long warned about, now becoming an urgent issue.

In response, President Trump has asked the Commerce Department to examine security risks from America's dependence on imported rare earth minerals. The U.S. Department of Defense has developed a warfighting enterprise that is significantly dependent on a supply chain closely tied to China. Recent developments pose a threat to the Pentagon's capacity to maintain this enterprise.

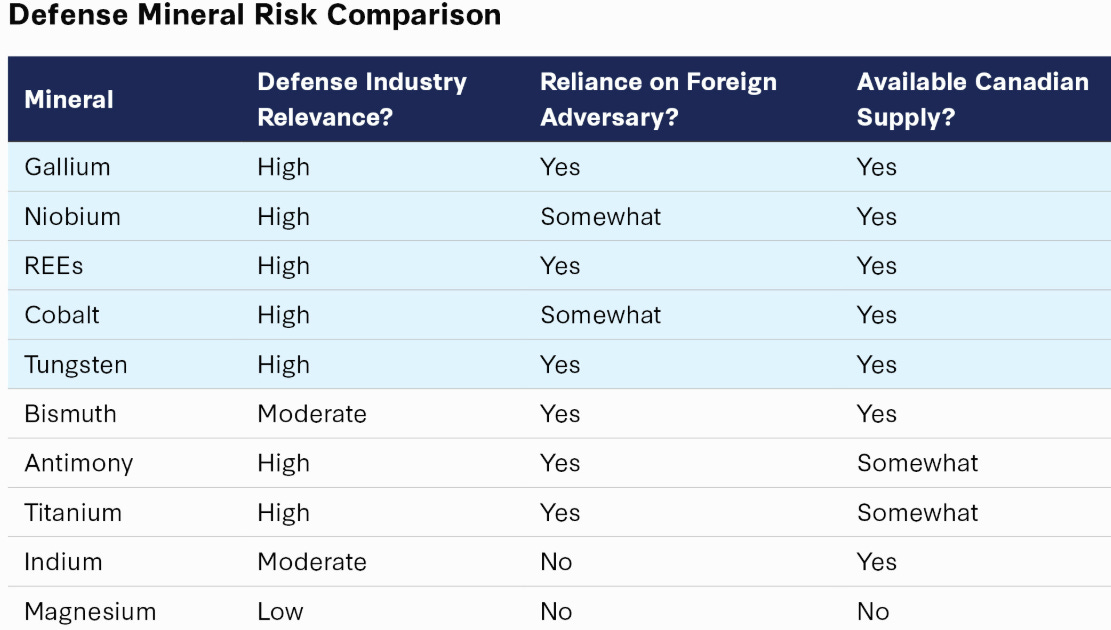

China is the leading producer of rare earth minerals, accounting for approximately 60% of the global supply. This dominance has raised concerns regarding supply chain security. The White House has expressed that America's reliance on imports poses a risk of "economic coercion." A shortage of rare earths could affect various sectors, including electronics, clean energy, defense, and medical diagnostic equipment. For instance, tungsten is used in armor-piercing rounds, and gallium is essential in radar systems.

In early April, Beijing implemented comprehensive export controls on seven rare earth elements essential for applications ranging from laser-guided weapons to MRI machines. The newly restricted elements—samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium—now require a government-issued license for export, with Chinese officials citing “national security” reasons for these changes. These measures follow similar export bans issued in December 2024 on gallium, germanium, and antimony—metals used in semiconductors, infrared optics, and armor-piercing munitions.

China's recent implementation of a licensing requirement, while not a total prohibition, will likely introduce uncertainty and restrict the steady availability of essential components to manufacturers. This measure, amid an already unstable global market, resembles Beijing’s 2010 response to Japan and illustrates the possibility of leveraging key supply chain resources for strategic purposes.

Since 2010, the Pentagon’s demand for components containing five critical minerals—antimony, gallium, germanium, tungsten, and tellurium—has surged, with contracts growing by 23.2% annually, and gallium-related contracts alone increasing by 41.8% per year. More than 80,000 distinct parts across 1,900 weapons now depend on these materials, affecting approximately 78% of all DoD weapons according to a new report by the Govini data analytics firm. The Navy leads in dependency, with over 91% of its systems containing at least one of these minerals. China’s export ban on antimony, gallium, and germanium resulted in prices for parts containing these critical minerals increasing by an average of 5.2% shortly after the ban, compared to procurements of those same parts prior to the ban. Specifically, components containing gallium saw a price increase of 6.0%, those with antimony rose by 4.5%, and components with germanium increased by 1.6%. All other parts experienced an average increase of only 1.4%.

The primary chokepoint is not in mining but in refinement. The United States often ships raw mineral precursors to China for processing and re-imports them as finished components. With Beijing’s 2024 export bans now expanded to include tungsten and tellurium, this loop is closing. Even antimony mined in Australia becomes unusable for U.S. systems if refined in China. Consequently, 88% of the DoD’s critical mineral supply chains are exposed to Chinese influence.

Nearly all antimony utilized in key platforms such as the F-16 fighter jet, Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, and Minuteman III missile undergoes processing through China at some stage. Only 19% is accessible without Chinese intermediaries. The strategic cost is evident—prices for gallium-containing parts increased by 6% within three months following the bans; antimony parts rose by 4.5%, whereas all other DoD parts increased by merely 1.4%.

Additional vulnerabilities exist beyond these five minerals. Magnesium—essential for airframes and missiles—is predominantly sourced from China and lacks a U.S. stockpile. The same applies to graphite and fluorspar, which are vital for rocket propulsion, lasers, and nuclear fuel processing.

A multi-faceted response is needed.

Firstly, revitalize domestic processing capacity. While the U.S. currently lacks domestic sources for gallium, germanium, and tungsten, recent federal investments have begun yielding results. For instance, the Kennecott mine in Utah has significantly reduced reliance on tellurium imports from 95% in 2019 to just 25% in 2023.

Secondly, the government must leverage mineral companionality—the occurrence of critical minerals alongside others. A zinc mine in Tennessee could potentially produce 30 tons of germanium and 40 tons of gallium annually, nearly matching China’s 2022 global exports of these materials. However, exploiting these sources requires regulatory reform, as most mining permits disregard companion minerals, thereby delaying extraction by years.

Thirdly, employ artificial intelligence and software to identify untapped byproducts across the U.S. industrial base, incorporating overlooked commercial suppliers into the defense ecosystem.

Lastly, strategic stockpiles must be expanded—and in some cases, established for the first time. Currently, there are no government reserves for gallium and tellurium, despite their critical status. DARPA has engaged AI company HyperSpectral to help address this critical issue.

The United States' reliance on China for critical minerals is a significant and increasing strategic vulnerability. If not properly addressed, this dependency could soon constrain U.S. deterrence capabilities, not due to financial or military strength, but because of elemental scarcity.

Related

China Halts Critical Exports as Trade War Intensifies

Trump orders tariff probe on all US critical mineral imports

How critical minerals became a flash point in US-China trade war

Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources