American Technology Firms and China’s Surveillance State

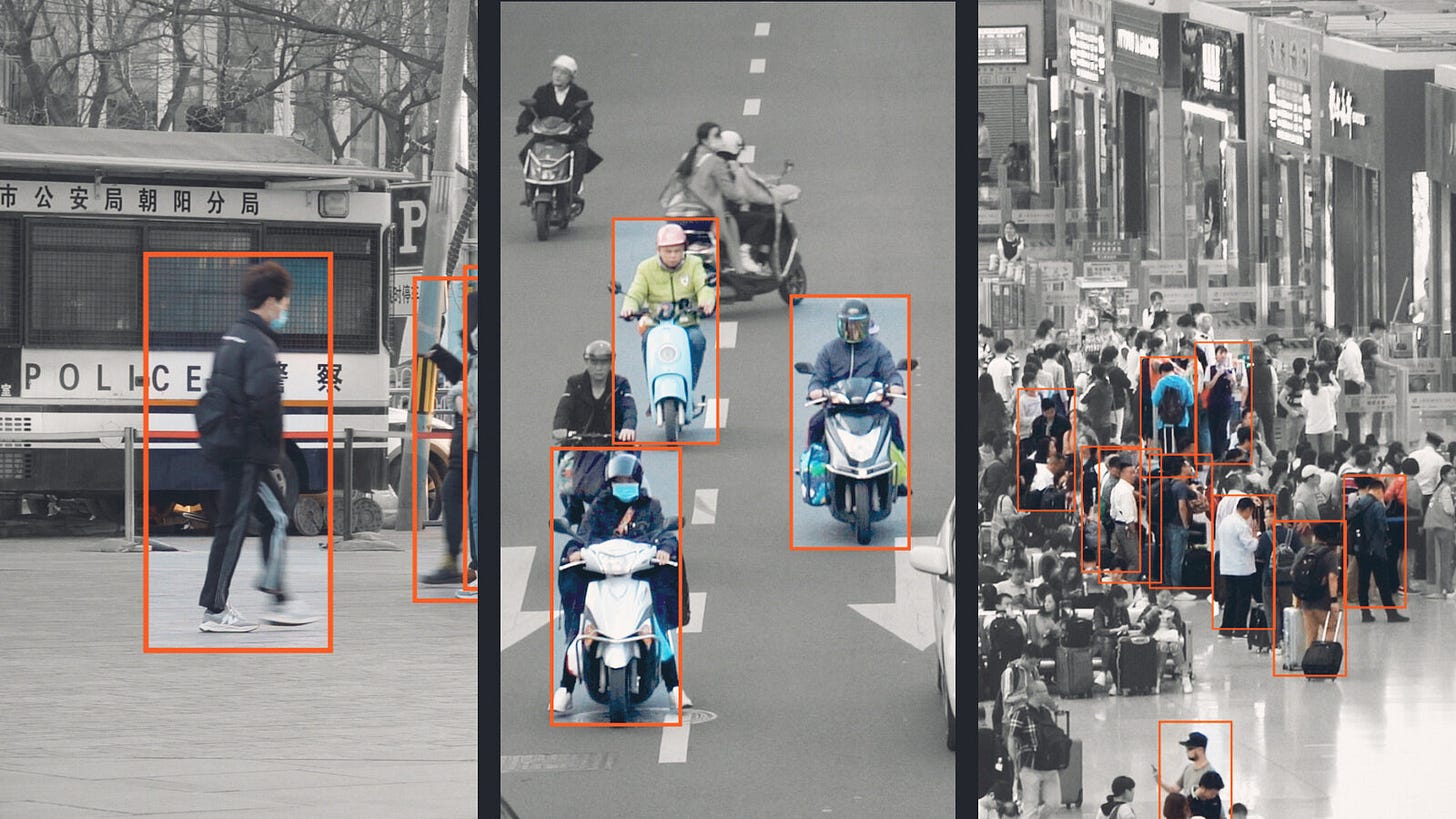

American technology companies were instrumental in designing and building China’s surveillance state, playing a far greater role in enabling human rights abuses than was previously understood. These firms sold billions of dollars’ worth of technology to Chinese police forces, government agencies, and surveillance companies despite repeated warnings from Congress and the media that such tools were being used to silence dissent, persecute religious groups, and target ethnic minorities.

A recent Associated Press investigation behind these findings drew on tens of thousands of leaked emails and databases from a Chinese surveillance company, thousands of pages of confidential corporate and government documents, public Chinese-language marketing materials, and procurement records provided by ChinaFile, a digital magazine published by the non-profit Asia Society. The AP also relied on dozens of open records requests and interviews with more than one hundred current and former engineers, executives, experts, officials, administrators, and police officers from both China and the United States. While American firms were by far the largest suppliers of surveillance technology, companies from Germany, Japan, and South Korea also played a role. The following examples are illustrative of what the AP uncovered.

In 2009, a Chinese military contractor collaborated with IBM, based in Armonk, New York, to design national intelligence systems, including a counterterrorism platform. According to classified Chinese government documents, these systems were later used by China’s Ministry of State Security and the military. IBM described these deals as “old, stale interactions,” insisting that if older systems are being abused today, such misuse lies entirely outside of IBM’s control, was never contemplated by the company decades ago, and should not reflect on its conduct today.

Throughout the 2010s, IBM representatives in China sold the company’s i2 policing analysis software to Xinjiang police, the Ministry of State Security, and other Chinese police units, according to leaked emails. A former IBM agent named Landasoft copied the software and used it to create a predictive policing platform that tagged hundreds of thousands of individuals as potential terrorists during the brutal crackdown in Xinjiang. IBM has stated that it ceased relations with Landasoft in 2014, prohibited sales of i2 software to Xinjiang and Tibet beginning in 2015, and has no record of i2 sales to the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau.

Other American companies also provided technology that directly supported ethnic repression. Dell and its subsidiary VMware sold cloud software and storage devices to police in Tibet and Xinjiang, continuing even as late as 2022 despite the widespread knowledge of abuses in those regions. In 2019, Dell advertised on WeChat that it had partnered with surveillance firm Yitu to sell a “military-grade” AI-powered laptop equipped with “all-race recognition” capabilities for Chinese police. Dell, headquartered in Round Rock, Texas, told AP that it conducts rigorous due diligence to ensure compliance with U.S. export controls. Oracle, based in Austin, Texas, and Microsoft, based in Seattle, also had their software integrated into Chinese policing systems, including in Xinjiang.

Fingerprint recognition technology was another area of foreign involvement. IBM worked with Chinese defense contractor Huadi to help construct the national fingerprint database, although IBM stated that it never sold fingerprinting-specific products and that any use of its systems for that purpose occurred without its knowledge or assistance. HP and VMware provided technology used by police for fingerprint comparisons. Intel, in its 2019 marketing materials, boasted that it had partnered with Hisign, a Chinese fingerprinting company supplying Xinjiang police, to improve fingerprint readers. Intel noted that the new device was tested in real-world scenarios with a municipal police bureau. Chinese media reports indicated that Hisign was still an Intel partner as recently as last year. Intel has since stated that it has had no technical engagement with Hisign since 2024 and pledged to act swiftly if it learns of credible misuse.

Facial recognition technology was widely promoted as well. IBM, Dell, Hitachi of Tokyo, and VMware all marketed such systems for use by Chinese police. Sony, another Japanese electronics giant, declared on its official WeChat account that it had wired a Chinese prison with “intelligent” cameras, claiming it was widely trusted for surveillance projects. Nvidia, based in California, and Intel both partnered with China’s three largest surveillance firms to add AI capabilities to video surveillance systems across the country, including in Xinjiang and Tibet, until sanctions forced a halt. Even more recently, Nvidia noted on its WeChat account in 2022 that Chinese surveillance firms Watrix and GEOAI were using its chips to train AI-powered patrol drones and gait recognition systems. Nvidia later stated that those partnerships no longer exist.

Collaborations extended into surveillance research as well. Nvidia acknowledged in a post dating from 2013 or later that a Chinese police institute used its chips for surveillance research. While Nvidia said it does not currently work with Chinese police, it did not address past activities. In 2021, an IBM researcher and a U.S. Army researcher co-authored a study on AI video analysis alongside a Chinese police researcher employed by a sanctioned company. According to the Army, the Chinese researcher only joined the project after the U.S. researcher’s work had been completed.

DNA surveillance also depended on foreign technology. Chinese police laboratories bought Dell and Microsoft software and equipment to store genetic data. Hitachi advertised DNA sequencers to police in 2021, and labs purchased pipettes from the German biotech firm Eppendorf last year. Massachusetts-based Thermo Fisher Scientific promoted DNA kits on its website until August, claiming they were designed for China’s national DNA database and tailored for the Chinese population, including ethnic minorities such as Uyghurs and Tibetans. The company even cited the work of a Chinese police researcher who, at a 2016 conference, described using Thermo Fisher kits to identify Uyghur and Manchu populations. Thermo Fisher stopped selling its kits in Xinjiang in 2021 and in Tibet in 2024 but continues to promote them to other Chinese police agencies, including at trade shows earlier this year. The company insisted its products are designed to be effective across global populations and cannot distinguish among specific ethnic groups.

Surveillance technology also extended into internet policing. In 2014, VMware acknowledged that internet police across China used its software. Two years later, Dell announced on WeChat that its services had assisted internet police in cracking down on “rumormongers,” effectively helping to promote censorship. An IBM marketing presentation, with metadata pointing to 2018, indicated that Shanghai and Guangzhou internet police used its i2 software, and the company held a Beijing conference promoting the product the same year.

Encrypted communications were another area of collaboration. Leaked government blueprints revealed that Motorola, based in Illinois, supplied encrypted radio systems for Chinese police to manage “sudden and mass events in Beijing.” Motorola did not respond to requests for comment.

American and Japanese companies also supplied the data storage necessary for surveillance. Seagate, Western Digital, and Toshiba manufactured hard drives specialized for AI-driven video surveillance. In 2022, Toshiba described in its marketing how such drives could help police identify and control “suspicious” or “blacklisted” individuals, explaining that they were optimized for security systems. Western Digital boasted of its partnership with Chinese surveillance company Uniview at a policing trade expo, months before Uniview was sanctioned for complicity in human rights abuses. Seagate, meanwhile, promoted its “tailor-made” hard drives for Chinese police AI systems on WeChat in 2022 and marketed them at a Chinese policing trade association earlier this year.

Mapping technology was also integral to police operations. Documents show that in 2009, IBM, Oracle, and Esri, the California-based creator of ArcGIS, sold hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of software to build China’s Police Geographic Information System. In 2013, HP marketed “digital fencing” solutions to Chinese police. These systems continue to alert authorities when Uyghurs, Tibetans, or political dissidents cross provincial or local boundaries. Although the United States restricted exports of such mapping software in 2020, the scope of those restrictions was limited. Esri still maintains a research center in Beijing that has marketed its services to police and other Chinese clients, though the company denies involvement.

Chinese police also relied on foreign consumer technology in their daily operations. Motorola walkie-talkies and Samsung microSD cards were used in body cameras. At police trade shows, Samsung promoted these products, while state-owned Jinghua advertised “AI-powered 5G” cameras under the Philips brand. Philips has denied any partnership with Jinghua, stating that it did not authorize sales of Philips-branded cameras in China and that it intends to address the matter with the company.

Many U.S. firms, including IBM, Dell, Cisco, Amazon Web Services, Seagate, Intel, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Western Digital, issued statements affirming their compliance with all export controls and regulations. Sony, Hitachi, and Eppendorf declined to address their operations in China directly but reaffirmed commitments to human rights. Other companies, including Oracle, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Broadcom (which now includes VMware), HP, Motorola, Samsung, Toshiba, Huadi, and Landasoft, did not provide responses. Microsoft asserted that it does not knowingly update software for China’s primary policing system.

Chinese authorities in Xinjiang defended their surveillance technologies as necessary tools to prevent crime and terrorism. Officials compared their practices to policing methods used in Western nations. Other agencies offered no comment.

Related:

THE CCP’S INVESTORS: How American Venture Capital Fuels the PRC Military and Human Rights Abuses